How to Improve Your Glutathione Status

Your body’s natural defence mechanism against cancer, autoimmune disease, environmental toxins and pathogens, and more.

If there’s one thing that I would recommend everybody do, it’s improve your glutathione status. It can help alleviate symptoms of all kinds of chronic disease, improve our ability to concentrate and perform difficult cognitive tasks, and help us meet and recover from physical challenges. Before I give you some ideas on how you might go about doing that, let’s start with an explanation of what glutathione is and what it does, and when we might be in need of more glutathione.

What is glutathione?

Glutathione (commonly abbreviated to GSH in academic publications) is the most abundant and most important antioxidant in the human body. Antioxidants are molecules that bind to what’s known as “free radicals” or reactive oxygen species.

If there is an imbalance between the amount of antioxidants in our body and the amount of free radicals, the free radicals can cause damage to our cells and/or parts of them, impairing their functioning and how they send signals to one another. This is known as oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress in small amounts can be important for adaptation to environmental conditions. It’s actually the mechanism by which we get fitter from doing exercise; our body responds to a moderate amount of oxidative stress with acute inflammation. This is inflammation that is local to the site of stress and should only last for a short period while the free radicals produced by exercise are removed and the body adapts to the exercise so that it’s more able to cope with the same stress the next time you exercise.

For example, if you were to start running for the first time in years, you would probably create some oxidative stress in your legs. Your legs would hurt a bit afterwards and might feel a bit fatigued. In a normal situation, your body would respond to the oxidative stress by creating more mitochondria so that you can produce energy faster the next time you run, reducing the oxidative stress on your muscles. This is what we would call a normal adaptive response to stress.

But if our oxidative stress is chronic we can create chronic inflammation. For example, if we don’t give ourselves enough recovery time between workouts for our body to clear free radicals and adapt, our workouts might end up doing us more harm than good.

Glutathione plays such an important role in detoxification of free radicals that it’s closely related to ageing and may be able to slow or reverse the ageing process. It’s an important mediator of oxidative stress and has been shown to be important in conditions as diverse as prevention of organ failure in COVID-19, gut health, and brain function. It is also implicated in many so-called mental health issues/diagnoses, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

When we might need more glutathione

Things that can negatively impact our levels of glutathione include psychological distress, high intensity exercise, a diet low in glutathione-containing foods or the amino acids that it is made from. Ingestion of or exposure to environmental toxins can also contribute to oxidative stress that depletes our glutathione. This includes drinking alcohol, as alcohol is shuttled out of the body via the liver by glutathione. Drugs and smoking can also deplete our glutathione levels, as can heavily processed foods (things like processed meats, two minute noodles, confectionary, and crisps) and mass-produced wines, as they contain high amounts of preservatives such as sulphur dioxide.

Low levels of glutathione have also been linked to leaky gut, as our healthy gut bacteria’s ability to produce glutathione is compromised.

There are also certain genetic conditions or predispositions which may affect our glutathione needs, such as variants of the MTHFR gene, which increase demand for glutathione if not managed properly. There also specific genes that might lead to impaired glutathione production.

Basically, because glutathione is our most abundant and most versatile antioxidant, it can be helpful in any situation in which we find ourselves subject to acute inflammation. Because it’s so helpful in clearing acute inflammation, it can prevent inflammation from becoming chronic.

How much glutathione do we need?

The amount of glutathione we need depends largely on what we are doing on a day-to-day basis and on what our environment is like. The more we are challenging ourselves mentally and physically, and the more toxins there are in our environment or diet, the more glutathione we are likely to need.

The exact amount is hard to pinpoint, because our individual genetics and ability to synthesise and use it vary a lot.

There are no known adverse effects to having as much as 1mg daily for six months, suggesting that this would be a safe minimum dose. But, if for some reason we have additional needs for glutathione, this may not be enough. If you were having this amount but were finding that you still had some kind of chronic condition, for example asthma, leaky gut, autoimmune disease, depression, etc, then it would be worth considering how you can increase your intake or improve your body’s use of the glutathione that you are already getting.

How do we get glutathione?

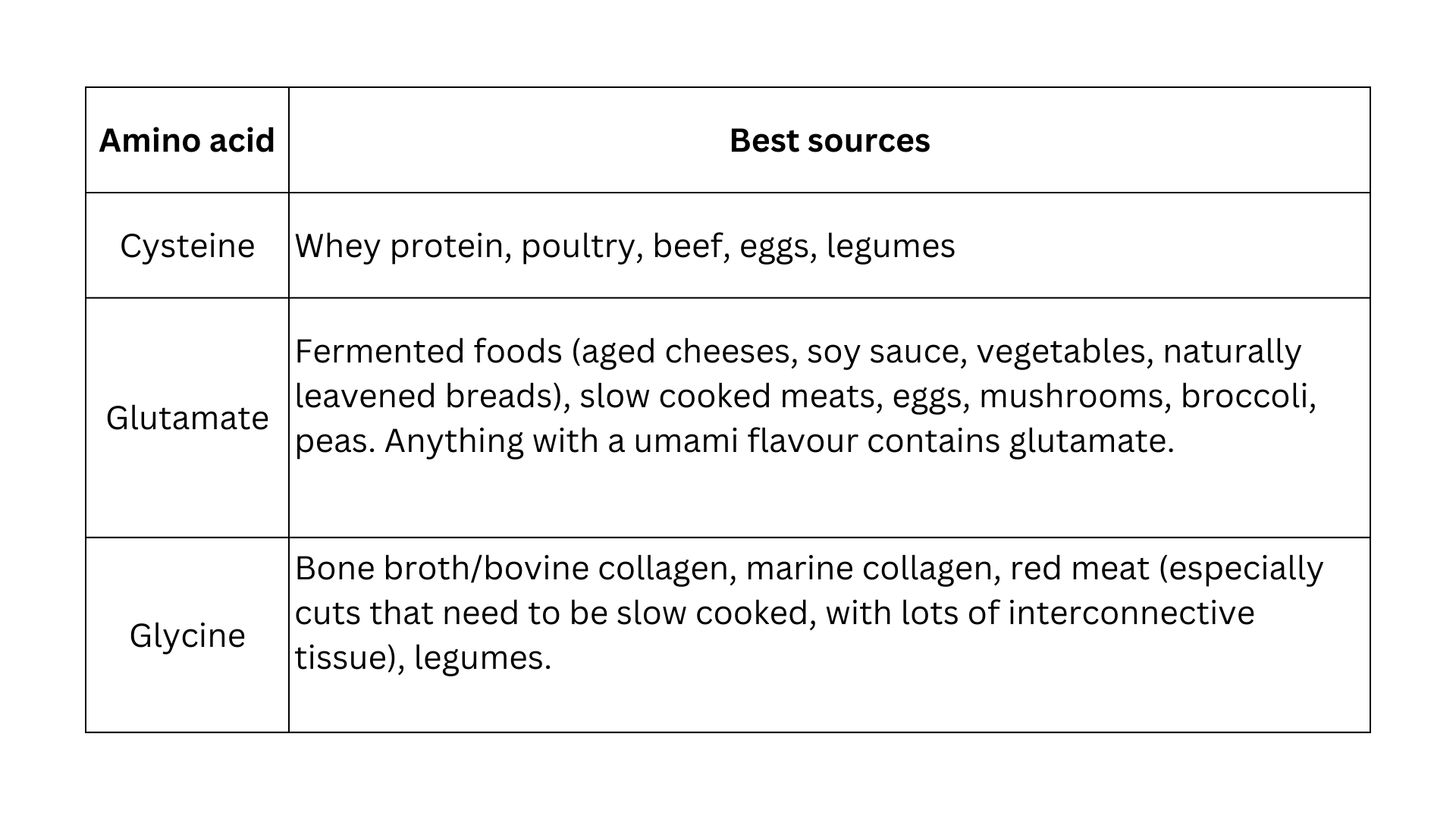

Glutathione can be made in the body, as well as being found in the food we eat. It is made in the liver from the amino acids cysteine, glutamate, and glycine. It is therefore important to get an adequate amount of these amino acids in our diet. Sources of each of these amino acids are listed below. Again, it’s important to acknowledge that individual needs may vary depending on a range of factors, such as oxidative stress, amino acid source (and therefore bioavailability), and genetics.

It’s also worth noting that other nutrients, both macro and micro, appear to influence glutathione synthesis, even though they are not the base substrate for it so a balanced diet of an array of nutrient-rich foods is the best strategy to managing glutathione status.

Many other antioxidants that we ingest in food have a hormetic stress effect on the body, acting as minor stressors that promote synthesis and release of glutathione. In other words, most antioxidants from plant foods don’t act directly as antioxidants but rather, as signals to the body to produce its own antioxidants, particularly glutathione. This is why a diet low in the amino acids needed to produce glutathione is likely to result in oxidative stress even if it contains plenty of antioxidant-rich but protein-poor foods.

In terms of macronutrient composition, a diet composed of healthy fats, high quality proteins, and quality carbohydrates will positively influence glutathione signalling in the liver.

And it’s worth noting that, while the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults ingest at least 1g protein per kg of body weight per day, this is a minimum requirement. Research suggests that as much as 2g/kg (or more, for elite athletes) may be a more optimal target for glutathione synthesis, amongst many other functions, within the body, though there is an adaptive period during which it’s normal to see a little added oxidative stress when protein intake is first increased.

Glutathione is also found as a complete molecule in food sources. It’s richest in red meat, eggs, and fish. Many vegetables are good sources of glutathione, while fruits tend to contain a little less.

Note that you can also obtain glutathione as a pure supplement (called liposomal glutathione), though this can be costly. A cheaper alternative is N-acetyl cysteine or NAC, which research suggests may be made more effective by taking it in combination with glycine. That said, a healthy, balanced diet ought to be the first resort for those seeking to increase glutathione synthesis.

How to Spare Glutathione

The other thing worth taking into consideration when trying to improve your glutathione status is how you might reduce your body’s actual need for it. Reducing the amount of toxins that we ingest or absorb is a really helpful starting point.

For example, if you reduce the amount of processed foods you eat each week, you would create less oxidative stress on your body. At the same time, you’ll likely be ingesting more foods that promote healthy glutathione production if you eat more nutrient dense, unprocessed foods. You can take it one step further by eating organic/chemical free foods and removing synthetic self-care and cleaning products from your routine.

But perhaps one of the least talked about, yet most important things you can do is decrease your body’s production of oxidative stressors. Most people don’t realise it, but every time we produce cortisol, we’re creating oxidative stress in our body, which depletes glutathione. This in turn can lead to DNA damage, which has implications for how our genes are expressed, which in turn impacts wellbeing. The good news is that that DNA damage appears to be reversible. The longer it is since we have experienced stress, the less DNA damage we show. If we can learn to manage our stress levels i.e. reduce our production of cortisol, then we can reduce the damage done overall.

Even better, if we increase activity of the Vagus nerve, we can boost glutathione production at the same time as we reduce the impact of stress on wellbeing.

Conclusion

In summary, glutathione is our body’s most important antioxidant. Glutathione depletion is associated with range of physical and mental health conditions and can be caused by oxidative stress and/or genetics. It is comprised of three amino acids, cysteine, glutamate, and glycine. We can synthesise it in the body from these amino acids, a process done in the liver. We can also get it directly from food, with meat, fish, eggs, and vegetables being the richest sources. Dietary supplementation is also possible, with liposomal glutathione being the best source, but a more cost-effective option is NAC, which should be taken with glycine to increase utilisation. We can also reduce toxins in our environment and from foods to reduce our need for glutathione.

Perhaps even more importantly, reducing stress leads to an improvement in glutathione status as we deplete less of it and increase our body’s capacity to produce it.

***

I work with people with chronic health conditions to manage and reverse disease. Want to work with me one-on-one to improve your health and wellbeing? Click on the link below to book your first session.